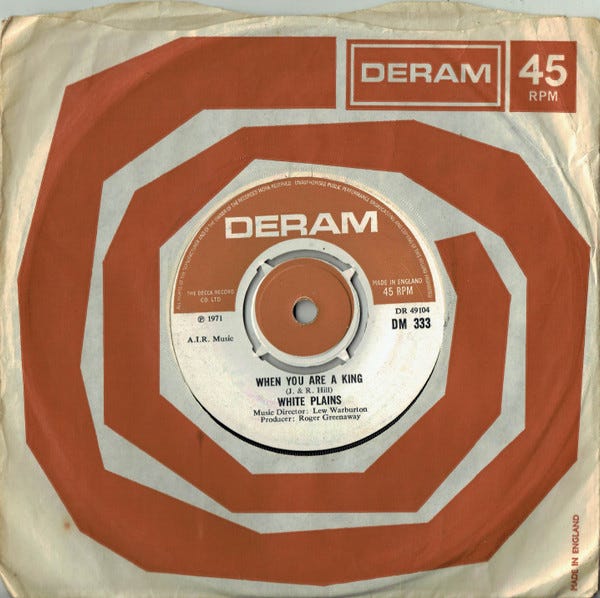

When You Are A King

Everywhere you go, people bowing low.

Paul Weller has an album of cover versions, Find El Dorado. Track #6 is, When You Are A King, a smash hit in 1971 for a group called, White Plains. It was written by Roger Hill and his brother, John, for whom I worked some 28 years later as a humble labourer. What can I say, gurus may be disguised and not even realise their true nature, flawed as they are by human foible.

I recognised that Universe must have placed me with Mr Hill in order to learn from him because the situation was so peculiar. It was no-status, poorly paid manual labour, working for an eccentric who idolised Margaret Thatcher and insisted upon starting work in the middle of the afternoon. He would pick me up en route to the job, where we’d put in an eight hour shift and it would be close to midnight by the time he dropped me back home, filthy and hungry, for £45 a day. I was approaching forty years old at the time.

We'd take a break around 6 or 7PM. John's wife, Jan - yes, John married Janet; they shared a Scorpio birthday - provided him with cheese and onion sandwiches on white bread and treacly instant coffee in a flask. I became addicted! John would offer me a cigarette - another currency of our relationship - and return to the topic of the day, as decreed by the Daily Mail. John wound me up to the point where I was about to snap. Then he’d extinguish his fag butt in the dregs of his coffee, throwing it out onto the floor (which I would later sweep) and calmly say, "Well, Russell, we don't have to agree about everything."

Politically, we agreed about nothing, but I came to understand that his deplorable views did not necessarily make John a bad person. Indeed, I began to find him more ridiculous than infuriating. We were working together at the time of the first London mayoral election. He thought Jeffrey Archer, the disgraced Tory peer, would be the best candidate. I pointed out that he was going to prison for perjury. John replied, "We don't know that. He ain't been convicted yet!"

I've never been called to jury service, but John had served twice. The second time, they made him the foreman of a jury that tried a chap whose estranged wife and kids had burned to death when the family home, which he had been obliged to vacate, went up in flames. The poor bloke had lost his family and stood accused of arson. The jury wanted to acquit him, but its foreman was convinced he did it. Eventually, John was obliged to concede a majority verdict of not guilty.

"He got away with it", John told me, trenchantly, years later. As, he believed, did the Guildford Four and the Birmingham Six, victims of two of the most notorious miscarriages of justice in British history, who were accused of IRA bombings. "They were fitted up and falsely imprisoned for crimes they had nothing to do with, John", I gently informed him. "Somebody did it!" exclaimed the King of Logic.

Speaking of The Troubles, the turning point in our relationship occurred around the anniversary of Bloody Sunday (when British troops opened fire on Irish Republican protesters on 30/01/72). John picked me up at midday on Saturday - he insisted upon working six days a week and would have done bloody Sundays, too, if her indoors hadn't objected - and we set off for Notting Hill. The gaffer observed that we might encounter some impediment en route, because a large demonstration was taking place around Hyde Park Corner to mark the anniversary. "I don't know what all the fuss is about", he said. "If you riot in front of armed squaddies and get shot, well, it's like going out in the rain and complaining about getting wet."

I did not respond. "Don't you agree?" he demanded. No, I did not agree. We were stopped at traffic lights, waiting for them to change. I swivelled my head to see John in profile, his eyes on the lights. The thought occurred that I could punch him hard in the ear, get out of his car and never speak to him again. But the moment passed. "Don't you agree?" he chivvied. I made an emollient remark and changed the subject. From that moment, John lost his power to antagonise me.

My dad had fancied himself as a DIY guy. Under the tutelage of John Hill, I began to see how inferior my father's skills had actually been. Tony Cronin took himself out of my life - this life - on 01/08/72 when he drove into a head-on collision on the wrong side of the road. They tried to tell me it wasn't his fault, but I was nearly 11 years old and not stupid. Plus, I saw the whole thing from the back seat. Decades later, my Dad's younger brother, Michael - who has himself recently passed, aged 91 - confided as he gave me a lift to the train station after another family funeral, "Your dad was the world's worst driver".

John Hill drove a big old Volvo saloon: the Silver Shark. It was a mobile tool box. Well, not just tools. I came to appreciate the phrase, "I've got one of those in the boot". It meant I could relax for half an hour while he went for a rummage. One time, John was even later than usual when he arrived to pick me up. He'd been rear-ended on the Old Kent Road and stopped to exchange insurance details. The hasty hatch back that charged into him was a write-off, but the Silver Shark was barely scratched.

The boot wasn’t John’s only trove. There was also the mythical space under his roof, back home in Lee Green. John had replaced the old hot water system with a combination boiler and intended to install stairs in the former airing cupboard space to facilitate access. He kept putting it off because he didn’t want Jan going up there. She might go on one of her de-cluttering binges and insist he divest himself of some of the precious things, as she had done with the garage.

One Monday, John informed me with some pride that he had been up early the previous day, in order to attend a flash sale at a hardware superstore, where he had availed himself of a new cordless drill at an advantageous price.

"Did you need a new Makita?", I asked. "No", he said, "but supposing I did? "I suppose you would then have to buy one", I reasoned, "and possibly pay full price." "Well, not exactly", he admitted. "I've got another one in the roof that I've not used". Now he had a back-up for the back-up. Was it any wonder Jan Hill was exasperated by the tool shop under her eaves?

Aside from tolerance of others’ opinions, the chief lesson I learned from John Hill was what used to be called the dignity of labour. Taking pride. With him, the aim was always perfection. A phrase I heard repeatedly in the early days of my indenture were, “No, mate, that’s not good enough. You’re going to have to do it again”. I had been somewhat diffident, but from John I learned about commitment. The importance of showing up and the imperative to bring one’s creativity to the job at hand in order to derive enjoyment from it.

John liked a challenge and was something of a native genius. Clients enjoyed working with him because he obviated pretentious architects. He had built for Claudio Silvestrin, King of the Shadow Gap, and remonstrated with him endlessly over the practicality of skirting boards to protect the base of a wall. Making it appear to float was all very well, said John, so long it was never accidentally knocked, in which case it could easily be chipped and the look would be compromised.

If and when architectural plans were presented, John would invariably deconstruct them and point out flaws. “Tell me what you want and I’ll find a way to do it”, he’d say to clients. Mostly, we worked around the houses of a circle of affluent friends in Notting Hill and Holland Park, where the rich people live. They tolerated John's schedule for his nous.

He barely moved his back teeth as he spoke, did Mr Hill, and smoked his way through his thought process. As situations got more fraught, his jaw tightened and he smoked more furiously. Some building conundrums might require as many as three Super Kings to resolve, one after the other in a chain. Because, when you are a King, then the cigs you smoke are Super.

John didn't want to get stuck in a groove. He once got involved in a project run by a crafty journalist who no doubt was able to write off the cost of her interior decoration as a business expense. She produced a big article in the Evening Standard nominating John Hill as, 'London's cleverest tiler' and giving his contact number. "It was a nightmare", he told me. "I had to turn my phone off for three weeks."

John and his brother Roger were like The Small Faces, smart East End kids of diminutive stature, having been raised on rationing. Debris, Ronnie Lane’s evocation of his post-war childhood, was one of John’s favourite songs. He was also partial to The Travelling Wilburys and had their 1988 CD in his car. Otherwise, John had pretty much lost interest in music, although he continued to receive annual royalty cheques for When You Are A King which has been covered many times - it may be the only song The Modfather has in common with The Nolans - and is included on numerous compilations, especially in Germany.

The initial success of their big hit gave the Hill brothers the opportunity to make an album, which failed to set the world alight. Faced with a young family to feed, John took odd jobs around recording studios, becoming the in-house maintenance man at AIR. Consequently, he was a fund of anecdotes of a particular flavour (see below). His preferred working hours remained those of the music biz.

While John became a jack of all building trades and master of most, his brother, Roger, acquired a reputation as a plumber to the stars. I was amused by the saga of Mark Knopfler's wet room, singing to the tune of Money For Nothing: "we’ve got to install a power shower / despite low pressure in the propertyyy". Roger never gave up on the songwriting and eventually retired from jacuzzi installation and relocated to Nashville to pursue his dream.

I learned next to nothing about building from John Hill. I did the dirty work of demolition and painted the construction after it was complete. Otherwise, my place was to watch what he was doing, anticipating what tool he might need next and handing it to him as required. Most thrillingly, I mixed up the muck. When plastering in a centrally-heated flat, where it's going off on the board as it’s spread on the wall, the knack is to supply the plaster in the correct consistency at just the right time. When you hit a rhythm and are not merely keeping up with your competitive plasterer, but pushing him, you become the co-dependent slave driver!

After the best part of nine months' hard labour, while paying me off at near midnight from behind the wheel of the Shark, as John Hill withdrew the builders' roll of fifty quid notes from his breast pocket and peeled off a precious few for me, he pronounced, "Well, Russell. Over the time we've been together, you have become a very competent labourer." Coming from him, it is the greatest compliment I have ever received.

Working for John Hill did not pay well, but it kept the wolf from the door and his back-to-front hours didn't give me much chance to fritter away what little cash I got. I was able to purchase my council flat with a self-certified mortgage based upon the previous year's accounts, when I still had the semblance of a career.

Subsequently, when I came to do my own place up, John came to work for me while I continued to work for him. I was both client and labourer. It was a cost effective arrangement and the quality of the tiling in my bathroom is highly impressive to the educated eye.

I continued to work for John as and when required, long after I'd learned the necessary lessons he taught me. I no longer needed to earn £45 a day getting covered in filth, but did it out of respect for Mr Hill and concern for his health. A lifetime of heavy smoking and not wearing a mask in dusty enclosed building sites had wreaked its toll on his lungs. Resentfully, he stopped smoking. If John needed some heavy lifting or demolition doing, I continued to show up to do his dirty work.

One Summer, we spent a few weeks together, happily constructing a garden railway. While so engaged, John Let slip that his older son was one of the first to take delivery of a new XJ series Jaguar, which I subsequently saw Clarkson review. "Sefton's new car cost £85,000", I informed his father. "Well, it's a nice ride, but that's more than I'd pay for a car", quoth the King of the Second Hand Volvo Saloon.

Sefton Hill's success is no secret; he is a millionaire game designer. John would admit he had resented having to shell out constantly to upgrade his sons' computers and games consoles as they grew up, "but the investment paid off". I'll say.

Games designers are 21st Century rock stars, with more money. Their products are less easily bootlegged and command reverence from younger generations who inhabit an imaginarium of virtual gameplay (I suppose). How rich are they? John Hill, who liked a challenge, supervised the installation of an indoor virtual golf course in Sefton's Essex mansion. His guests - rich geeks flew in for the weekend on private jets - could virtually play any of the world’s classic golf courses chez Sefton. "It takes a lot of processing power", acknowledged Mr Hill, senior.

The last time we met was in late 2012. I called John to replace the RO cartridges on my under-counter water filter, which he had installed. While I had been FUBAR and functionally blind, a clumsy friend had cross-threaded the screw and I needed Mr Hill to sort it out for me, which he duly did. John was very short of breath, but still missing the fags. He confided that his boy kept finding jobs for him to do to prevent him from taking on more stressful work. Also that he occasionally used an oxygen cylinder at home.

The next time I called Mr Hill, seven years later, he was still with us, said his wife, who answered his phone, but barely. John had had a terrible accident. Watching telly late at night as was his wont, he got up to get a snack from the fridge but did not cart his oxygen tank into the kitchen with him. He passed out and gashed his forehead on the counter-top, peeling back his scalp from his skull. Janet Hill awoke to find her husband drenched in blood before her like an apparition from the Scottish Play.

John recognised my name, but could not bring himself to speak to me. I didn’t delete his number, but have changed phones since then and its no longer listed in my contacts. I can’t imagine the geezer remains extant, post-Covid. Thanks, John, my liege. You were indeed a King and a difficult person to love, but I managed.

John Hill's top three tales of recording studio shenanigans:

#3 UFO

A dodgy British hard rock group of the 1970s, UFO spent several weeks recording an album at AIR. John Hill loathed them, especially the drummer, who insisted upon having his kit set up on a riser in the main room even though it made no difference, sonically. At least they didn't wear Spandex in the studio. Or not to my knowledge.

UFO made their record, mixed it and it was ready to roll. They arranged a listening party for the record company execs, to be held in the studio after a celebratory meal at a Soho trattoria. The master tape was cued up so that, upon their return, they had only to press, 'play'. Unfortunately, when they did so, nothing happened. All the assembled listeners heard was tape hiss.

While UFO & co were at dinner, John Hill the handyman had seized the opportunity to fiddle with something in the control room. It involved stretching across the console. He didn't know what happened, exactly. Perhaps the unbuttoned cuff of his jean jacket brushed a sensitive switch?

Whatever, the master tapes of UFO's freshly-recorded new album were accidentally erased. Sorry!

#2 Rod Stewart

The main room at AIR, overlooking Oxford Circus, was very grand and had a listed interior. In order to cut the sonic boom, a ceiling of acoustic tiles had been suspended high above the musicians' heads, beneath the actual old ceiling.

Once upon a time, Sir Roderick of Stewart, accompanied no doubt by The Faces and inevitably somewhat slightly sloshed, carried away by the exuberance of his vocal performance, hurled an empty wine bottle through the false ceiling. I like to think it was a Mateus Rosé bottle.

The bottle displaced one of the acoustic tiles and did not come down. John was obliged to retrieve it and replace the tile, which was easier said than done, given the height of the room. He had to build up staging in order to climb up there and reach it, but whenever he tried to do so, some arrogant rock star would come in and tell him to piss off out of it. And that imperious star was usually Sir Paul McCartney!

#1 The Sex Pistols

The Pistols recorded Never Mind The Bollocks... at AIR's sister studio, Wessex Sound. John Hill claimed not to know who they were, which leads me to assume his story pertains to an early session with Dave Goodman, before the Bill Grundy incident in December 1976 conferred tabloid notoriety upon the four snotty spikey tops. John found them to be a bunch of idiots who permitted their entourage to vandalise the premises he maintained without apparently realising that they would pay for the damage out of their pocket.

The limits of Mr Hill’s endurance were breached when one of the filthy herberts gobbed on his freshly-painted wall. When John rolled in one afternoon, he was outraged to find a huge ball of phlegm like a slug congealing there. Perchance Sid Vicious himself, then just a part of the retinue, had expectorated? Sid is credited, if that is the right word, with having originated that disgusting punk performance.

Mr Hill did not concern himself with whodunit. He just wanted it cleaned up. Indignantly, John Hill burst into the Sex Pistols recording session, bringing it to a halt, and read them the riot act. Who did they think they were and what did they think they were doing by creating unnecessary work for ordinary, working class people? “You're not a gang of rebellious anarchists, you're just a bunch of bad-mannered wankers. And you won't be doing any more recording until you've cleaned my f-ing wall”, he dictated.

A junior member of the entourage was duly delegated and John Hill taught the naughty punks a vital lesson in respect!